Academia’s leadership challenge is that almost none of us have been trained to manage people, much less other academics; almost none of us have significant, sustained leadership development opportunities; most academic chairs are happy to step back into faculty roles. Emotional Intelligence can help us be more effective and resilient, as leaders and as members of the department team.

This article is the first in a series. Here at the outset, I’d like to define awareness (as a foundation for emotional intelligence) and then share a three-stage awareness-building exercise that—while it does entail considerable reflection and emotional work—can be done quickly, even amid all the pressures of a department chair’s week. When I’ve worked through this exercise with other chairs, it has helped develop self-awareness and awareness-of-others. Later, in the articles that follow, I’ll share further ideas and exercises that are intended to help chairs (and other academic leaders) to develop strategies for navigating the workplace in what is hopefully a healthier way—and to build greater resilience over time.

“I’m aware of that…”

I am a philologist. I say this without too much self-deprecation or, to be truthful, apology, but it is relevant here because – like all of our disciplinary influences and training – it fundamentally shapes the way I view the world. Have you ever considered the bewildering variety of nuanced ways “aware” is used in English?

“I’m aware of that.” dismissal

“We have recently become aware that…” explicit warning

“I’m aware that …” best case: empathy without compromise

“Are you aware that…” implicit warning

“I’m aware of the issue…” at worst, condescension, but hopefully reassurance

So what does “awareness” mean for a department chair? Some chairs I’ve worked with love to frame awareness in terms of mindfulness; others have had such negative experiences with mandatory meditation workshops or with teachers who set the expectation that one’s mind must be empty to meditate, that even the word “awareness” provokes resistance. The irony is that both reactions are facilitated by awareness, emotion, and memory. When you hear a noise in the middle of the night in your house and listen intently, that is awareness. When a bedraggled student appears at your office door (or zoom room) and you do a double take to re-assess what might be going on, that is awareness. When the email program pings and you look up from the task you should be doing to look, that is awareness. You have noticed and directed your attention. When you see that the email is from you-know-who, then read the subject line or the email and start to feel that feeling or to write that brilliant reply in your head or start the self-talk that just really isn’t very productive … that is when we get to deploy our emotional intelligence to drive our decisions and behaviors. It starts with awareness, noticing, devoting attention.

Awareness is the ability to notice relevant input, to perceive – out of the mass of information we sort through in our interactions with ourselves and others – what we should be thinking about and how it might matter. In that sense, awareness is foundational because it is sine qua non: you cannot build and demonstrate emotional intelligence without first being aware.

What is Emotional Intelligence?

Emotional Intelligence (EI) is, at root, the understanding of emotions, how they affect our behaviors and decision making, how our behaviors affect other people and their emotions, and how all of that has an impact, for example, in the workplace.

EI as a workplace concern in the modern period (recognizing that the basic ideas around EI exist in many traditions and in many periods) moved out of academia and into popular awareness in the mid-1990s. Since then, a number of assessment models have entered the suite of workplace assessments, and there has been an increase the understanding of EI as a significant factor in employee satisfaction and discretionary effort, as well in customer satisfaction and even clinical outcomes for patients. Most recently, attention has turned (there has been some compelling research in this area) to the effect of EI on team performance and cohesion. These are often the kinds of terms that turn academics off but, whether we like them or not, efficacy, creativity, inclusion, belonging and teamwork are essential for the challenges we face in higher education.

Why should we care about EI?

When I speak with chairs about EI solutions, there’s often that point in the conversation where someone says a version of, “What does that have to do with our workplace?” I’ve found that two responses used in tandem help clarify: “If you don’t think it might have significance for your workplace, why are we talking?” and “If your people bring their brains to work, they bring their emotions to work.” Emotions and memory have extensive connections to our neurochemistry and also to each other, and that we can sometimes actively affect our mental and emotional states, for example through breath regulation. This leaves us in an interesting place, where we are profoundly affected by memory and emotion as we experience and react to events but where we can also engage our judgment centers to self-regulate, make choices, and build new memories. Awareness is the tool we can use to become more mindful and to respond to our emotions, the emotions of others, and their effect on situations and decision-making. Without awareness we are, simply put, reacting without judgment to the world around us.

As academics we are trained, and certainly acculturated, to think that rationality is prime. Often, as a consequence, because emotions are thought to be irrational, they are undervalued. I have a lot of problems with both ideas but won’t attack them here. How about just this: there’s a curious reaction in the academy to people with “too much” passion or people who can’t “control themselves,” and yet we prize teachers who can inspire students and leaders who can show empathy and “lead with heart.” The Academy values rational thought, careful argument, and objectivity, and yet, the Academy also functions in large part because there are people among us who step up for leadership roles and who develop capacities and skills for managing people, very often in circumstances that are not terribly rational, where arguments are not always careful, and where objectivity is unreachable. So, whatever illusions we might foster about objectivity and rationality, when it comes to working together or to leading in higher education, emotions and emotional intelligence matter at least as much as the skills that make us successful researchers.

Why should a chair care?

Emotional Intelligence and the awareness that supports emotional reasoning are even more significant, I would argue, on the academic side of higher education leadership because as an industry we are, well … different. Our institutional structures organize us into something like little affinity groups with forced cohabitation and shared resources, of much longer duration than almost any other industry. In fact, even though “stars” sometimes move (or used to — the drops in senior position hires across the large disciplines are sobering), the rest of us will very likely spend our whole career not just at one institution but within one department. (Ironically, leadership talent is one of the major ways to move, which in the best-case scenario takes the most EI competent person out of a department.) Some of our most toxic and pervasive relationship problems might not resolve until an individual leaves, retires, or dies, but many if not almost all other issues can be either remedied or mitigated by emotional intelligence development and strategies. As chairs, emotional intelligence is critical to us because we are often at the nexus not only of administrative concerns in the department but of the personal ones too. So, even if we don’t want to use our leadership to directly address the emotional intelligence dynamics of our departments, we can be more effective chairs and help ourselves manage our own responses. And, if we engage in focused development, we can become more resilient leaders and, frankly, happier people. But it all starts with awareness.

Inward-Outward Awareness: Notice – Engage – Empower

Awareness inward, of our own emotions and their effects, is the best place to start. One of the principles to be mindful of, however, is the idea of reciprocal effect: when we notice and make changes inward there is an outward effect on our behaviors, and when we start to notice the behaviors of others there is often an opportunity to build greater inward awareness. So, this initial exercise, while it is focused on self-awareness, will likely generate an outward effect in your day-to-day interactions with other people. The purpose of the exercise is to build awareness of our emotional intelligence habits, the reactions that happen when certain kinds of input are received, and our emotions and memories triggered. Becoming aware of our habitual reactions allows us to change them into situational, chosen responses. What you ultimately choose to do may be the same. It’s the process you want to affect.

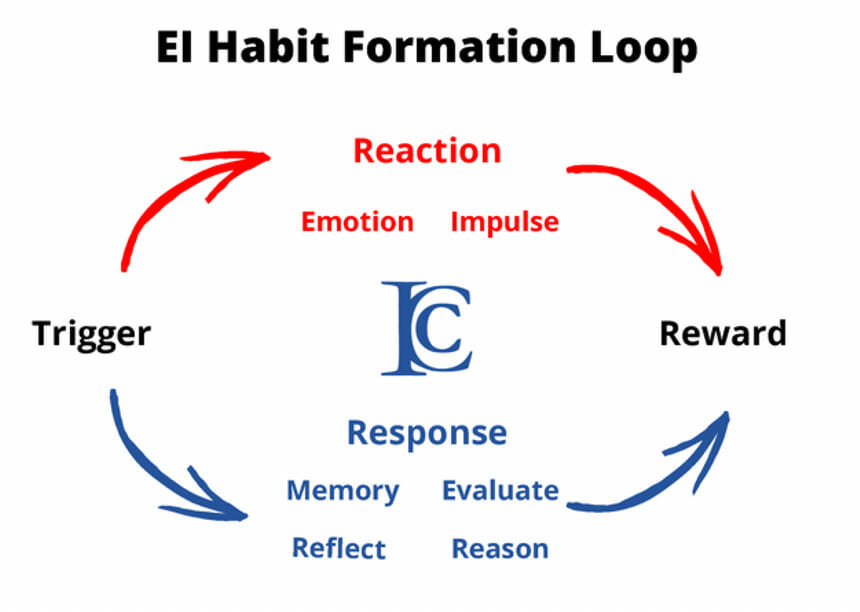

When we experience an event, we are triggered and the reaction-reward loop (top of image, in red) kicks in. Let’s call this the reactivity cycle. The “reward” may be pleasant or unpleasant in a general sense, but its effect is to reinforce the reactive behavior. This is how all habits are built. If we want to interrupt the habit, we need to adopt a strategy to interrupt the reaction-reward. Emotional Intelligence models tend to explain these strategies in terms of emotional reasoning (bottom of image, in blue), in which we evaluate the emotional state, its relevance for the situation, and how this input can be used to choose a response. “Respond, don’t react,” as the saying goes. As chairs, we have little time and many demands on our attention, which makes developing a practice of respond, don’t react difficult. I’m sure that each of us could come up with a list of the things that tend to derail our plans for a day, or that make our work within our department difficult, or that suddenly appear on our to-do lists or calendars. But the long and short of it is that our days can be volatile and unpredictable. We need ways to build new habits that we can use to regulate our responses to the unpredictable (or frustrating) things.

So here is an exercise in emotional reasoning that takes little time yet can yield significant results. It has three stages. You can do the stages separately and over the course of a week. All you’ll need is a little time each day, a journal or a way to keep notes, some self-discipline to keep at it, and a healthy dose of goodwill for yourself. Be gentle with yourself as you take on a practice like this.

Notice – Record

If you are interested in development, you are ipso facto capable of it and aware that it takes time and effort. So, while it is frustrating and sometimes discouraging early in a process of development to pause, the pause to Notice is a critical first step. For the reactivity cycle (which we are essentially learning to short-circuit), it’s necessary to notice not only when you react but what the circumstances are around the reaction. Because we’re human, we focus on what we perceive to be negative reactions as the places to develop first; this is fair enough. But we should also notice our positive reactions, from which we can learn just as much and through which we can build capacity to respond well. The first strategy, then, is simply to notice, using a variation on the time-tested W5 method.

Schedule some 5-10 minute slots in between your meetings or, if you can, take 5-10 minutes after an interaction that went really well or really poorly. It’s also okay to do this at the end of the day – but much better to do it shortly after the interaction. Take a slow count of 10, breathing gently at a comfortable pace; then, in your journal, quickly, without pausing to consider the exact words, write down HOW you reacted, WHO was there, WHEN it happened, WHERE it happened, and WHAT happened as a result. You don’t need to think about WHY – “why” is too easily the gateway to unhelpful justifications or to litigating the past. What we’re after are the facts around the interaction so you can begin to diagnose your EI behavior patterns. Remember to notice a good interaction, too!

Engage – Imagine

One of the major obstacles to development around the reactivity cycle is finding distance, so we can build new neural pathways for new behaviors. Many factors play into this problem, from chemistry to attitude. Once we’re triggered, it is very hard (maybe impossible) to work on making a change in the moment. One of the ways we can calm our reactivity is to adopt a mindfulness practice. Such a practice can use the brain’s plasticity to build new connections, bringing down levels of stress hormones, supporting the functioning of the hippocampi, thereby helping to move information into the judgment centers. But early in our development, in the moments of stress, it’s hard to be calm. So, we have to make time to work on our own with some of the conditions under which we reacted – in this way we can be ready for next time.

The Stoics had a similar practice called exercitatio (which actually just means “practice”). With exercitatio, they imagined as precisely as possible a situation that causes distress and used emotional reasoning to reflect on solutions. Sometimes the solution was centered around key precepts, which could be used to short-circuit the emotional reactivity by promoting emotional reasoning. Other times, the solution was to focus on the naturalness of an event (e.g., death) in order to reframe the emotional reaction in a more positive and appropriate way.

The second stage of the exercise, then, is to Engage and imagine in order to begin establishing a new pattern of reaction. Set aside 15-30 minutes towards the end of one day in the week. Consider what you learned about the interactions that you recorded in the Notice stage. Choose one person or event, trying to recreate the interaction as clearly as possible. As you work your way through the scenario in your head, you may notice specific words or actions that you remember very clearly, and others that are less clear. Once you’ve worked through the scenario at least once (don’t change it!), you may feel yourself having an echo of the emotional reaction. Now evaluate the reaction and try to give it a label. But be honest – sometimes the first label we give can be re-evaluated and our understanding of what we were feeling can be refined.

For example, I might first think that I am angry at a senior colleague who seems to be challenging me, but what I might actually be feeling is mistrusted. Reflect in your journal on the specific interaction, the point at which you think the interaction started to go sideways, and the emotions you think you might have been feeling. In the relative safety of the replay, you will begin to shift perspectives and build self-awareness.

Empower – Shift Perspective

When all is said and done, we can only regulate ourselves and can only be accountable for our own actions. But our actions do not happen in a vacuum; there is always an outward effect. When we shift our perspective, we can shift focus away from our own reactions and attempt to see the situation from the viewpoint of another person. This awareness of others is very important for emotional intelligence and for empathy. Eventually, by shifting perspective effectively and often, you will become a more empathetic leader – but you will also get better at receiving empathy and kindness from others.

The third step in the exercise, then, is to attempt to adopt the perspective of another in the situation you explored in the Notice and Engage steps. If it is too personally difficult to adopt the perspective of the other person/people directly participating in the situation, that’s totally fine. Instead, try to imagine being a bystander, with a focus on yourself. Now that you have explored the situation and the feelings you were experiencing, how would the other people in the situation (or this outside observer) experience you having those feelings? You don’t need to be negative about yourself, nor positive – just be honest. You know yourself well. Did you express your frustration, for example? How directly? Do you have a pattern of pushing down feelings? What memories did that interaction activate? What did you do and how might others have perceived your behavior?

Try hard – this is very difficult – to watch yourself have those reactions. Can you become aware of the effect you had on the other people affected in the situation? Again, we’re not focusing on blame or praise; we want to use the earlier steps as building blocks toward becoming aware of others and especially of the effect our reactivity has on others and on the difficult situations in which we all find ourselves.

Bringing it together

Our emotional experience of the academic workplace is embedded in our habits and prior experiences. Our neurological makeup is such that emotions are built into our memory systems and activated in every interaction. When we engage honestly, with self-awareness, around the “Notice – Engage – Empower” steps, we are starting to build new emotional memories through which to filter the next interactions. This work is the most important of all, and the hardest to achieve. Formation of new habits follows from consistency and success.

We can bring it all together by adopting one small “disruptor” practice, which we can use to interrupt our habitual emotional reaction in the kind of interaction explored over the stages of the exercise. This gives time for the emotional reasoning loop (which is “slower” than the emotional memory generated through the amygdala) to activate. This disruptive practice can be anything that simply halts a reactive behavior. For example, a common issue I see with many busy chairs is pace in reply. Email, Slack, whatever – the fast pace of reply can lead to misunderstanding, lost information, more need to negotiate meaning and intent back and forth, etc. The disruptor practice you could adopt is to set a hard rule that you will not reply to an email without at least 15 minutes passing between opening it and replying. The potential disruptors are many, but their goal is the same – to draw out the response cycle so that you have time to practice the insights you gained through reflection and use emotional reasoning.

The first phrase any new language learner should learn is “Please, slow down.” It is the same with your internal emotional vocabulary. You need to buy time to let the new memories process and to regulate yourself effectively. For the interaction you choose to reflect on, what might be a useful disruptor? Can it be something as simple as ending the meeting? Taking a slow breath? Refusing one-on-one meetings with that person? How will you practice this new kind of awareness and agency as you build your emotional intelligence?